Pathans in Our Midst – II

Two Pathan dynasties ruled India – the Lodhis and the Surs. The reign of one, the Lodhis, was long but its imprint on history was limited. The reign of the other, the Surs, was brief but it left behind an indelible mark.

The history of Pathan rule, especially that of the Lodhis, is based on very sketchy historical sources and it is difficult to tease out history from fable. Accounts of the period abound in tales of miracles, curses and mystic powers. The writings of religious figures dominate the source materials for the period. One such important account, Waqiat-e-Mushtaqi, was written by a Shaykh, Rizqullah Mushtaqi. These accounts also relate the enormous power wielded by Sufi Saints. Their power is not merely spiritual. Many are also active in the political sphere. There are instances of aspiring emperors requiring their intercession to acquire power. A Sufi’s blessing could secure a throne and a curse could overturn it. All these elements make a reading of the history of the period very colorful though somewhat incredulous.

The Lodhis (1451 – 1526)

Bahlul Lodhi, the founder of the Lodhi dynasty was orphaned at a very young age and was brought up by his uncle Sultan Shah Lodhi, who ruled the jagir of Sirhind during the reign of Muhammad Shah of the Sayyid dynasty. Bahlul succeeded his uncle to the jagir and quickly gained the confidence of Muhammad Shah who rewarded him with more territory in Punjab including Lahore. His ambition soared and he eyed the throne of Delhi. His opportunity came when Muhammad Shah’s effete successor, Alam Shah wore the crown. Alam Shah, lazy and disinterested in the business of ruling, moved to Badaun leaving the capital to his relatives to govern. Bahlul, sensing the weakness of the Sayyids, effected a coup. The rule of the Sayyid dynasty came to an end. The Khutbah was read in Bahlul’s name and the rule of the Lodhi dynasty began in 1451.

Like so many founders of a dynasty, Bahlul spent a large part of his reign waging war and annexing new territories. The Sayyids had ruled a shrunken empire. The Sharqi Sultans ruled from their capital in Jaunpur in eastern India and posed the most significant threat to Bahlul. For nearly thirty years, beginning 1452, the two waged a series of inconclusive wars each ending with a precarious truce. Finally, Bahlul defeated the Sharqi rulers in 1484 and annexed large parts of their territory. By the end of his reign, Lodhis held all territory from Punjab to the border of Bihar.

Bahlul was regarded a just ruler who was munificent in his behavior. Mushtaqi recounts “He accumulated no treasures. Every territory that he seized after a battle, he distributed it among the nobles and soldiers, and maintained a brotherly intercourse with them. ” He was a pious man who held Sufis and Shaykhs in great regard and it appears they reciprocated. As Mahmud Sharqi knocked on the doors of Delhi in 1452 with odds stacked in his favour, Bahlul prayed through a tense night at the tomb of renowned Sufi Saint, Bakhtiar Kaki. Divine intervention was swift. The inimitable Mushtaqi relates ‘Early in the morning a man appeared from the heaven and handed over a staff saying, “Go and hit these few drowsy fellows who have come”.’ The staff it appears was very effective. Sharqi’s forces were repulsed and he left Delhi in a huff.

Bahlul died at the age of 80 in 1489 having ruled for 38 years. He had appointed his second son, Nizam, as his successor but this did not prevent a succession war from breaking out. The faith of Nizam’s mother, who was the daughter of a Hindu goldsmith, militated against him. Nizam, however, remained steadfast, making all the right moves, including a visit to the leading sufi of Delhi, Shaykh, Sama-ud-Din, who blessed him. The same Shaykh, it appears, conferred on him the name Sikandar, the Indian name for Alexander the Great.

Sikandar Lodhi’s rule, according to the accounts, is presented as some sort of utopia. The generous Mushtaqi recounts “Sultan Sikandar was a great king, devoted to sharia. He loved justice and excelled in bravery and large-heartedness. During his reign, people were prosperous. Agriculture and the work of building construction increased considerably. The soldiers enjoyed immense prestige. The traders used to travel in his country with a sense of security. The artisans and the peasants passed their time is contentment. There prevailed such peace and order in the vilayet that the robbers and highwaymen submitted on their own, became law-abiding and settled down to live peacefully.”

The same accounts also seem to suggest that Sultan Sikandar was a bigot. It is possible the biographers, owing to their own religious inclination and worldview, exaggerated his zeal for Islam just as they appear to overstate the fabulousness of his rule. Sikandar was a patron of the arts and learning. His love for music and his decision to have major works of music translated from Sanskrit to Persian do not seem to suggest an overzealousness for Islam. He may have even consumed wine. Even the story of his death, probably apocryphal, appears to contradict his image as a zealot. A Sufi Saint, Shaykh Abdul Wahhab, exhorts the Sultan to keep a beard in accordance with Islamic custom. Sikandar does not take the advise seriously, and once the Shaykh leaves, does the unthinkable: he mocks the Sufi. The enraged Sufi curses Sikandar, prophesizing that the mocking comment would stick in his throat. Unsurprisingly, the Sultan soon develops a disease of the throat which does not allow him to eat or drink. Death follows. The Alexander of his times, it appears, owed both his ascent to the throne and exit from the world to Sufi Saints.

Sikandar was succeeded by his son Ibrahim in 1517. Ibrahim lacked the qualities of his father and grandfather. To accommodate the fiercely independent character of Pathans, Bahlul and Sikandar, had struck a delicate balance between the egalitarianism of the Pathan tribal system and the centralizing tendency of autocratic rule. Ibrahim Lodhi upset this balance as he attempted complete control over his Pathan chiefs. Given the Pathan spirit, dissent was inevitable. Babur, who was knocking on the doors of India, received an invitation from Daulat Khan Lodhi, Governor of Punjab to invade the land. Ibrahim Lodhi and Babur clashed on the plains of India’s most celebrated battlefield, Panipat, in 1526. Ibrahim Lodhi lost despite numerical superiority thus ending the reign of the Lodhi dynasty.

Lodhis are one of the less celebrated dynasties of India. However, this does not diminish the significance of the period. According to historian I.H Sidiqui, in the Afghan period “The gulf between the conquered and the conquerors of Hindustan was bridged and the process of the integration of Hindu and Muslim cultures was not only accelerated but almost completed in certain areas of North India. The Muslims began to exhibit keen interest in the sciences of the Hindus while the Hindus learnt Persian and manned the state department of finance.” The period also witnessed a spiritual efflorescence. Two of the greatest figures of the Bhakti movement, Kabir and Nanak, whose teachings were to have a profound influence on the subcontinent, preached during this period. Sufis were not to be left behind. According to Sidiqui “some of the distinguished Shattari (an order of Sufis) saints were deeply influenced by the Hindu mystical practices which they tried to adapt to Muslim concepts. Sayyid Muhammad Ghaus Gwaliori (a leading Shattari saint) popularized Hindu mystical practices amongst the Shattari saints through his translation of Amrilkund and established identity of connection between Muslim and Hindu mystical terminology.”

Lodhis reputation as builders is barely recognized. Sikandar Lodhi founded the city of Agra, which became the second capital of the dynasty. Agra remained important even after the decline of the Lodhis: it served as the capital of the Mughals for a considerable period. Elegant Lodhi monuments, with their seeming double-storied facade and niches at two levels, dot the Delhi landscape. Of all the dynasties that have ruled Delhi, none have left behind as many monuments in the city as the Lodhis.

The newly established Mughal dynasty would rule from 1526 to 1540 till the advent of another Pathan dynasty – the Surs.

The Surs (1540 – 1555)

Sher Shah, the founder of the Sur dynasty, whose original name was Farid, was born to a minor noble probably in the year 1486. His grandfather, having failed as a trader in Afghanistan, migrated to India during the reign of Bahlul Lodhi seeking employment as a soldier. He secured employment in the service of a Pathan noble and eventually obtained a jagir at Narnol in the vicinity of Delhi. His son, Hassan, inherited the jagir. Hassan’s patron was transferred to the East and he was awarded the parganas of Sasaram and Khawasapur in Bihar. Farid was the oldest of Hassan’s sons and the likely successor to the two jagirs, but the machinations of a conniving step-mother, who eyed them for her own son, drove Farid to leave his house at the age of twelve. He moved to Jaunpur, then a major centre of learning. There young Farid immersed himself in learning and at a later stage secured employment in the revenue department. Father and son reconciled after an estrangement that lasted ten years and Farid was given the responsibility of managing the two parganas. Farid’s administration of the jagirs was brilliant. Farid put in place administrative reforms that he was to replicate when he ruled India

Historians can’t seem to agree how Farid acquired the name Sher Khan. According to the more popular, though somewhat less credible version, while on a hunting expedition Farid and his patron, Bahar Khan, the Governor of Bihar, were attacked by a tiger. Farid moved swiftly and slayed the tiger with his sword. The grateful Governor conferred on him the title Sher Khan, the Tiger Conqueror. Whatever the truth behind the title, there is little doubt that Sher Khan had the daring of a tiger. He also had the cunning of a fox tempered with an ability to carefully weigh all options before making a move.

It is possible to provide here only a brief outline of Sher Khan’s dazzling rise to the throne of Delhi. The conniving step-mother yet again affected Sher Khan’s expulsion from his father’s house, this time by using the highly effective expedient of denying her husband a place on her bed. The step-mother’s machinations proved to be a blessing for Sher Khan. Left alone to fend for himself, he moved to Agra, which was the second capital of the Lodhis. He cultivated powerful friends and gained employment in the service of Daulat Khan, a powerful noble of Sikander Lodhi. Sher Khan’s father passed away in 1520 and Daulat khan secured for him the jagir of Sasaram.

Sasaram was a mere stepping stone. In the space of twenty years, Sher Khan grew from being the ruler of a modest fiefdom to becoming the Emperor of India. Sher Khan, the master strategist, tiger and fox rolled into one, employed all possible means on this spectacular journey – military might and trickery, magnanimity and perfidy, diplomacy and bribery. He closely tracked the developments in North India and when his fellow Pathans, the Lodhis, lost to Babur, Sher Khan aligned himself with the Mughal. He gained Babur’s confidence and was awarded more territory in the east. With the passing of his patron, Bahar Khan, Sher Khan became the de facto ruler of Bihar. He now set his eyes on Bengal. He defeated Mahmud Shah, the ruler of Bengal, in a series of battles and the crown of Bengal was within his grasp. The Mughals at the time were consolidating their empire in India and a conflict with the rising pretender from the East was inevitable. In 1539 and 1540, Sher Khan and Humayun, Babur’s successor, fought two battles. Humayun came off worse in both and barely managed to escape with his life on either occasion. After the first battle, Sher Khan proclaimed himself the emperor: khutbah was read in his name and the coins that were struck too bore his name. Sher Khan thus became Sher Shah.

In the next 5 years, Sher Shah displayed inexhaustible energy as his sword scythed through the country felling rulers in quick succession. His biographer, K.R Qanungo, writes of the extent of his rule, “He became the master of territories from Indus on the West and the hills of Assam in the East; the Himalayas on the North and the Satpura range on the South.” These brilliant victories would have earned him an honourable place in the rolls of India’s renowned military conquerors But Sher Shah was special; more than just a military conqueror. He was among the rare characters that history marks for greatness; among the few who leave behind an imprint that is visible for centuries.

It is possible here to provide only a glimpse of his extraordinary contribution to building institutions many of which survive to this day. He was a brilliant administrator and according to many historians the foundations of Akbar’s fabled administrative system were really laid down by Sher Shah. His apprenticeship at Sasaram served him well. Qanungo writes, somewhat gushingly, of the far-reaching impact of the administrative reforms he initiated at Sasaram, “It was Farid who gradually built up a well-knit revenue administration at this time, which was to become the archetype of the revenue system of his empire, and which again was to be passed on to the Mughal and the British empires to come down to free India almost intact”. Even historians who do not agree with Qanungo’s sweeping views acknowledge that Sher Shah’s administrative reforms were a defining stage in the evolution of the administrative system in India. Sher Shah inherited a chaotic system which he very quickly organized into a three-tier system –at the Centre, Sarkar and Pargana level. The administration of the pargana was divided into a civil and police function. A similar dual administrative system existed at the Sarkar level. The essential elements of the system survive to this day in India. In the 1921 version of his book, Qanungo compares the positions of Sher Shah’s officials with those in British India “The modern Magistrate and Collector of British India is the official successor of the Shiqdar-i-Shiqdaran of Sher Shah and the Tehsildar that of the Amin.”

The administrative system allowed Sher Shah to reform the revenue system. The peasant in India had often been subjected to a brutally exploitative system of taxation. Sher Shah ordered that all lands were to be surveyed under a uniform system of measurement. The expected revenue from the land was assessed for every village in a pargana under the direct supervision of the amin. A third of the expected revenue was taxed in cash or kind. Sher was fair but firm in his approach and his orders to revenue officers were “be lenient at the time of assessment but show no mercy at the time of collection”.

Sher Shah seemed to understand intuitively that the economy would flourish if the taxation system was simplified and infrastructure was created to support trade and commerce. Goods were taxed only at two points: one at the frontier and the other at the point of sale. Infrastructure was created at a frenetic pace. He restored the old imperial Grand Trunk road from Sonargaon near Dacca to the Indus, making it the envy of highways in the medieval world. He built three other major roads: connecting Agra to Buhranpur; Agra to Jodhpur and Chittor; Lahore to Multan. These roads served as the arteries of the empire which allowed trade to flourish. An estimated 1700 serais (rest-houses), two kos apart, some of which still survive, came up on these roads. The serais were secured like a mini fortress and organized to provide B&B like comfort to travelers. Hindus and Muslims, forever wary of being polluted by the other’s food, were provided separate quarters and cooks. Brahmin cooks serviced the Hindus thus ensuring the highest standards of purity. The economic response to such an infrastructure stimulus was swift: market-towns quickly developed around the serais.

Sher Shah’s most lasting creation is, of course, the Rupee. Sher Shah inherited a chaotic currency system which he, with his characteristic efficiency, organized into standardized gold, silver, and copper coins. The silver coin, which weighed 178 gms, was given the name Rupiya (Rupee). The Rupee continued largely unchanged in this form into the 20th century till the advent of paper currency and new forms of the rupee coin.

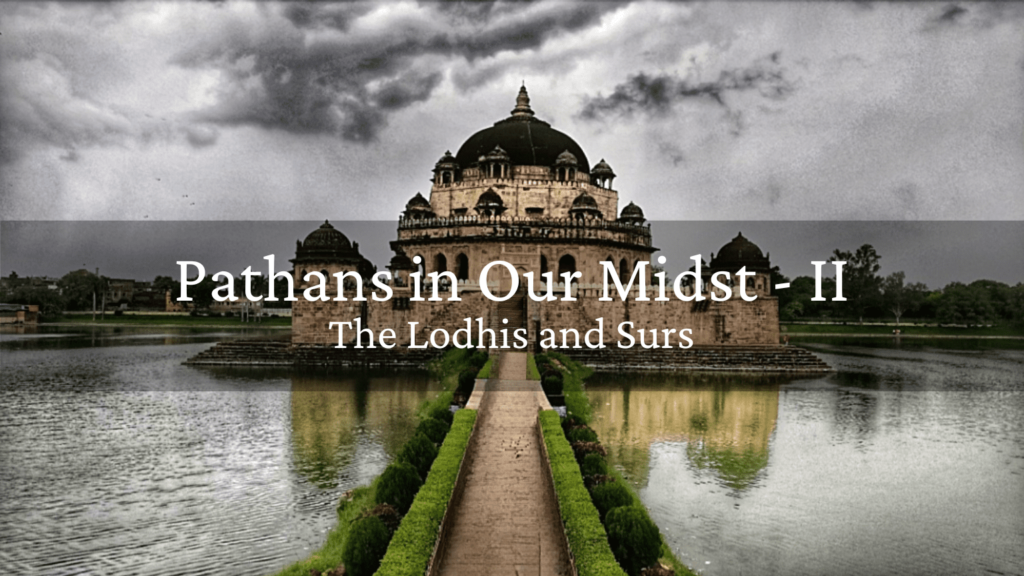

Sher Shah, forever a man of action, fittingly, died in battle. In 1545, at the siege of the fort of Kalinjar, which was the gateway to Bundelkhand, a shell exploded and killed him. Sher Shah, the Tiger among Kings, was laid to rest at the place from where he began his remarkable journey: a magnificent tomb at Sasaram marks his resting place.

Sher Shah was an extraordinary ruler. There is certainly a case to be made for making the reading of his reign mandatory for modern-day politicians. Sher Shah ruled for five years, a period which coincides with the tenure of elected governments in most democracies. It is not uncommon for elected leaders, having failed in their tenure, to complain that five years is too short a period to bring about meaningful change. Sher Shah’s rule demonstrates what a visionary ruler, with an ability to execute, can achieve in a short span of time.

Sher Shah was succeeded by his second son, Islam Shah, after a customary succession war. Islam Shah was distrustful of his father’s senior Pathan nobles and ruthlessly eliminated most of them. Accounts of the period present him as being exceptionally cruel and deceitful but on the whole his reign provided stability. He was an efficient administrator. According to Qanungo “Islam Shah ruled the Afghans with an iron hand, but nourished the peasantry and merchant folk as tenderly as his father”. A fistula caused Islam Shah’s death at the age of 32 in 1553. The next two years were a chaotic period as a messy succession war saw the crown change heads many times. The instability ultimately caused the demise of the Sur dynasty as Humayun, the fugitive Mughal who Sher Shah had twice humbled, returned to reclaim the throne of Delhi in 1555.

With this, the Pathan rule in India would come to an end. Pathans would not rule India again except for a brief two- year period in Independent India when an erudite Pathan would become the ceremonial ruler of India.