The Poet and his Murshid – II

Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya was arguably the most influential Sufi Saint of the subcontinent who would play a seminal role in the spread of Sufism. Seven centuries after they passed away, the towering murshid and his inseparable murid, continue to rule from their graves.

The Murshid

Khusraw is undoubtedly one of the greatest geniuses the subcontinent has produced. His life, however, cannot be viewed in isolation. History, sometimes, chooses to create its great characters in pairs; the life of one so conjoined with the other that they are inseparable. Such is the story of Khusraw and his greater half, Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya. We now turn to the life of this Sultan of Saints – the Sultan-ul-Auliya.

Nizamuddin was truly the master of the realm. In his presence even the most exalted seemed to pale into insignificance. So overpowering, it appears, was his aura that even his closest confidant, Khusraw, could not sit in his presence for too long and was forced to take a break to regain his composure. Khusraw stated “when I am in his presence, there is trembling feeling in me”. He further explained in a couplet

How can one see one’s face in it?

Nizamuddin, whose grandfather migrated to India from Bukhara, was born in Badaon in present day western UP in 1238. He was an infant when he lost his father which, according to one account, occurred in somewhat dramatic circumstances. Nizamuddin’s father fell ill and his mother, Bibi Zulaikha, dreamt that she would have to choose who between the father and son would survive. The agonized woman chose her son. Her choice, as subsequent events were to prove, was wise. Bibi Zulaikha, a woman of great piety and a role model for those spiritually inclined, was to play a profound role in shaping Nizamuddin’s character. Mother and son had to endure great poverty but in the middle of these indigent circumstances she didn’t waver from providing to her son the best education that Badaon could offer. Badaon, was a thriving centre for fleeing Central Asian scholars, poets and mystics. It was under a leading Islamic scholar that Nizamuddin received his early education. Nizamuddin, however, yearned for learning greater than what Badaon could offer. He urged his mother to move to Delhi.

Delhi, the throbbing educational and cultural centre, was as harsh to impoverished migrants then as it is today. The family lived in great poverty, endured many days of hunger and suffered many evictions as they moved from one accommodation to another. But the commitment to education remained unflinching. Nizamuddin was tutored by many eminent scholars and finally received his ijaza (certificate), the approximate equivalent of a modern Doctoral degree, from one of the great scholars of Delhi, Maulana Zahid.

His true calling, however, was in the spiritual world. He had heard of the great Sufi mystic, Farid, in his adolescent years and the yearning to become his murid grew with every passing year. Nizamuddin briefly flirted with the idea of obtaining a Government job in Delhi but realized soon that a higher calling awaited. He packed his modest belongings and left for Ajodhan in Punjab, the home of Farid. Farid was the head of the Chishti silsila (order) of Sufism.

Farid was nearly 90 when he met Nizamuddin, but age did not dim his keen eye. He seemed to sense a spark in Nizamuddin and took him under his wing. Under the supreme master, Nizamuddin completed his spiritual training and imbibed the central tenets of the Chishti order. Farid, much to the consternation of his sons, passed on the stewardship of the silsila to Nizamuddin saying “I have given you both the worlds. Go and take the empire of Hindustan.”

Nizamuddin became the head of the Chishti silsila in 1267. For the next 5 decades he was the undisputed ruler of the spiritual empire. The Chishti silsila was founded in India by Muin-ud-din Chishti. The different silsilas of Sufism, while following broadly the same tenets, developed their own methods of guidance and practices. Nizamuddin, who was fourth in the line of Chishti masters in India, possessed an extraordinary vision and exceptional organizational ability which expanded the reach of the mystical movement greatly and turned it into a mass movement. At the core of Sufism lay esoteric concepts which engaged the minds of the finest scholars and philosophers but these ideas lay beyond the reach of humbler minds. Sufi saints often attempted to adopt suitable means to simplify these concepts for the masses. Nizamuddin’s genius lay in combining the finest elements of mass transmission – narration of anecdotes for simplifying complex concepts and the use of vernacular language for doing so. This was combined with the free serving of food(langars) to all without distinction at the Khanqahs (lodges). The nourishment of both the soul and the body was an irresistible blend. More than 700 khailfas (senior disciples), tutored by Nizamuddin himself, would spread to different parts of the country and found many Khanqahs. People flocked to the world of Sufism.

Nizamuddin’s khanqah at Ghiyaspur was a hive of activity. Gifts in the form of money, cloth and food flowed to the treasury. All manner of people – impoverished and rich, meek and powerful – came in droves for spiritual healing. Though Nizamuddin rejected miracles he, according to his biographer Nizami, “possessed nafs-i-gira (intuitive intelligence) of a very high order. He could read a man’s motives on his face”. While Nizamuddin rejected miracles, he seemed to be able to heal by touching an inner chord that would draw upon the visitor’s innate strength and conviction. Of Nizamuddin’s power to heal Khusraw would write:

Thousands of mountains of grief have melted away

One of the most interesting aspects of Nizamuddin’s life was his relationship with the ruler of the earthly empire, the Sultan. Farid had laid down the terms of engagement “If you aim to achieve the spiritual position attained by our elders, keep away from the princes of the blood”. Nizamuddin was scrupulous in following these instructions. No Sultan was permitted in his khanqah. Nobles of the Sultan, as much in need of the spiritual touch as the commoner, however, were not restrained from following Nizamuddin and so flocked to his khanqah. Seeing his powerful nobles at the feet of the Saint, understandably, made the Sultan jittery but for much of Nizamuddin’s reign, with some notable exceptions, a fine balance was struck between these two power centres of the empire.

When this balance was upset the Sultan seemed to have come off worse. Mubarak Shah, the impetuous and debauched Sultan, sought the complete subservience of Nizamuddin when he assumed power. The custom of the time required eminent persons of Delhi to attend the Sultan’s court on the first day of every month. The Sultan expected Nizamuddin’s presence. Nizamuddin sent his servant instead. The enraged emperor ordered his presence the following month and emissaries were sent to Nizamuddin to warn him of the consequences of not complying. As the day approached several followers urged the Saint to acquiesce The Sultan was depraved, they reasoned, and could therefore cause grave harm. Nizamuddin refused to budge. As the fatal day dawned, Delhi was on a knife’s edge. Tension was palpable. The contest was reaching its conclusion. A calm Nizamuddin told his followers “Last night I saw in my dream a bull rushing towards me. I caught hold of its horn and pushed it back”. A few hours later news was received that the Sultan had been brutally murdered in a move orchestrated by his favourite General and lover, Khusraw Khan. The impetuous bull was laid to rest.

According to chronicler Ferishta’s account, end of the formidable Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq came in a similar vein. This claim is contested by most historians but such is the power of Nizamuddin’s legend that the story persists to this day. Ghiyasuddin apparently was displeased with Nizamuddin on two accounts. One, his love for sama (music) and secondly for not complying with his order of returning the cash given to the Khanqah by his predecessor, Khusraw Khan. Nizamuddin informed Ghiyasuddin’s emissaries that the cash, as was the custom of the Khanqah, was distributed to the poor soon after its receipt and therefore could not be returned. The explanation did not satisfy Ghiyasuddin. The victorious Sultan returning from his conquest of Bengal, sent a farman ordering Nizamuddin to leave Delhi before he reached the capital. An unperturbed Nizamuddin replied “Hunuz dilli dur ast” (Delhi is still far) Ghiyasuddin’s son had planned elaborate celebrations, on the outskirts of Delhi, to receive the triumphant emperor. But the preparations were made in a hurry. A hastily constructed wooden pavilion collapsed and claimed the life of the emperor. Delhi did prove to be too far.

While historians may dispute the reliability of these fascinating anecdotes, Khusraw was quite clear where, between the Sultan and the Saint, the balance of power lay. He wrote:

But the rulers stand in need of the dust under his foot

The Poet and his Murshid

At first glance, Nizamuddin and Khusraw seemed an odd pair. Khusraw was a man of the world, fond of the good things in life and a servant of the Sultan who would write qasidas in his honour. Nizamuddin, on the other hand, was frugal beyond belief, shunned regal company and was a strict disciplinarian who devoted so much time to prayer and meditation that he hardly slept. But this is a deceptive reading of the two characters. Khusraw, his qasidas notwithstanding, was essentially a poet of the spirit. The worldly ambitions of youth gave way to a quest of the mystical as he matured. Nizamuddin, for all his abstemious ways, was no dour saint. He had a keen sense of humour, enjoyed poetry and was unusually fond of music.

Khusraw became a follower of Nizamuddin in 1273 but it was many years later that the two, when Khusraw permanently settled in Delhi, came close. Khusraw visited the Khanqah almost every day. Nizamuddin, affectionately called him Turkullah (Turk of God) and looked forward to his visits. He was the only person permitted in Nizamuddin’s room in the night. Khusraw, the supreme raconteur, carried with him tales of the intrigues and scandals of the court which the saint was quite happy to hear. The interest in the tales may not have been merely for the entertainment they provided. For Nizamuddin, whose power and popularity made him susceptible to the machinations of insecure Sultans, it was important to keep a tab on the twists and turns of courtly life.

Nizamuddin’s fondness for Khusraw was that of a master for his most special disciple. And beyond. It was a bond that opened the doors to Nizamuddin’s closest inner circle. He once said to Khusraw “I tire of everyone, but not of you.” The Saint’s sharp intellect and discerning eye recognized Khusraw’s special talent. Of his poetry, Nizamuddin remarked “Khusraw, like whom few men have written poetry or prose, is certainly the king of poesy’ realm.” He also seemed to have a great respect for the depth of Khusraw’s ideas. While reviewing one of his works, Nizamuddin commented “God has leavened all the organs of Khusraw’s body with wisdom and learning for he swims all day long in the sea of ideas and brings out a hundred thousand pearls”

Khusraw, on his part, was a blind devotee, an unquestioning faithful for whom Nizamuddin was the supreme master at whose feet lay deliverance. He expressed his devotion in his inimitable style:

Find peace in your soothing words,

The lowly Khusraw will have an eternal life,

Since he became your slave for a thousand lives

He also had great respect for Nizamuddin’s knowledge and wrote:

His knowledge illuminated the two worlds

So devoted was Khusraw that he credited his extraordinary poetic talent entirely to Nizamuddin even if it meant altering some facts. In an oft repeated story, Khusraw seeks from Nizamuddin a prayer for sweetness in his poetry. Nizamuddin takes a bowl of sugar from under his bed and spreads it on Khusraw’s head. Unsurprisingly the request is granted and Khusraw’s poetry acquires sweetness. Khusraw writes “From him I found such saliva that has given such a lustre and freshness to my poetry.” Khusraw was already an established poet, known for the “lustre” of his poetry, when this episode is supposed to have occurred but he was quite happy to give the credit for the sweetness of all of his poetry to his master.

Khusraw, the courtier, was in the pay of the Sultan but he was quite clear where his loyalty lay. The newly crowned emperor, Jalaluddin Khilji, founder of the Khilji dynasty, aware of Nizamuddin’s diktat forbidding Sultans from entering his khanqah, decided to visit the place without prior notice. Khusraw learnt of this and informed Nizamuddin. The plan had to be dropped and an infuriated Sultan summoned Khusraw. Khusraw defended himself by stating “In disobeying the Sultan I stood in danger of losing my life, but in playing false to my Master, I stood in danger of losing my faith”.

The Murshid and Murid were inseparable not only in life but also in death and the afterworld. Nizamuddin passed away in 1325. Amir Khurd, Nizamuddin’s devoted follower and biographer, relates Khusraw’s reaction when he heard of the news “He blackened his face, tore his shirt, and rolling on the ground came towards the hovel of Sultan- al-Mashayikh with torn clothes, weeping eyes and blood racing in his heart. Then he said “Oh Muslims! Who am I to grieve for such a king, rather let me grieve for myself for after …… I will not live for long.” He is also supposed to have recited the Hindavi couplet:

Chal Khusraw ghar apne, rain bahe sab des

Lets’s go home, Khusraw, evening has set over the world.

The evening had set and six months later Khusraw followed his master to the grave.

Nizamuddin had wished to share his resting place with his inseparable murid. He is believed to have said “He is the keeper of my secrets and I shall not set foot in paradise without him. If it were lawful, I would have instructed you to bury him in the same grave with me so that we two may always remain united”. The laws of Islam forbade such a practice so Khusraw was buried in a separate grave a few feet away.

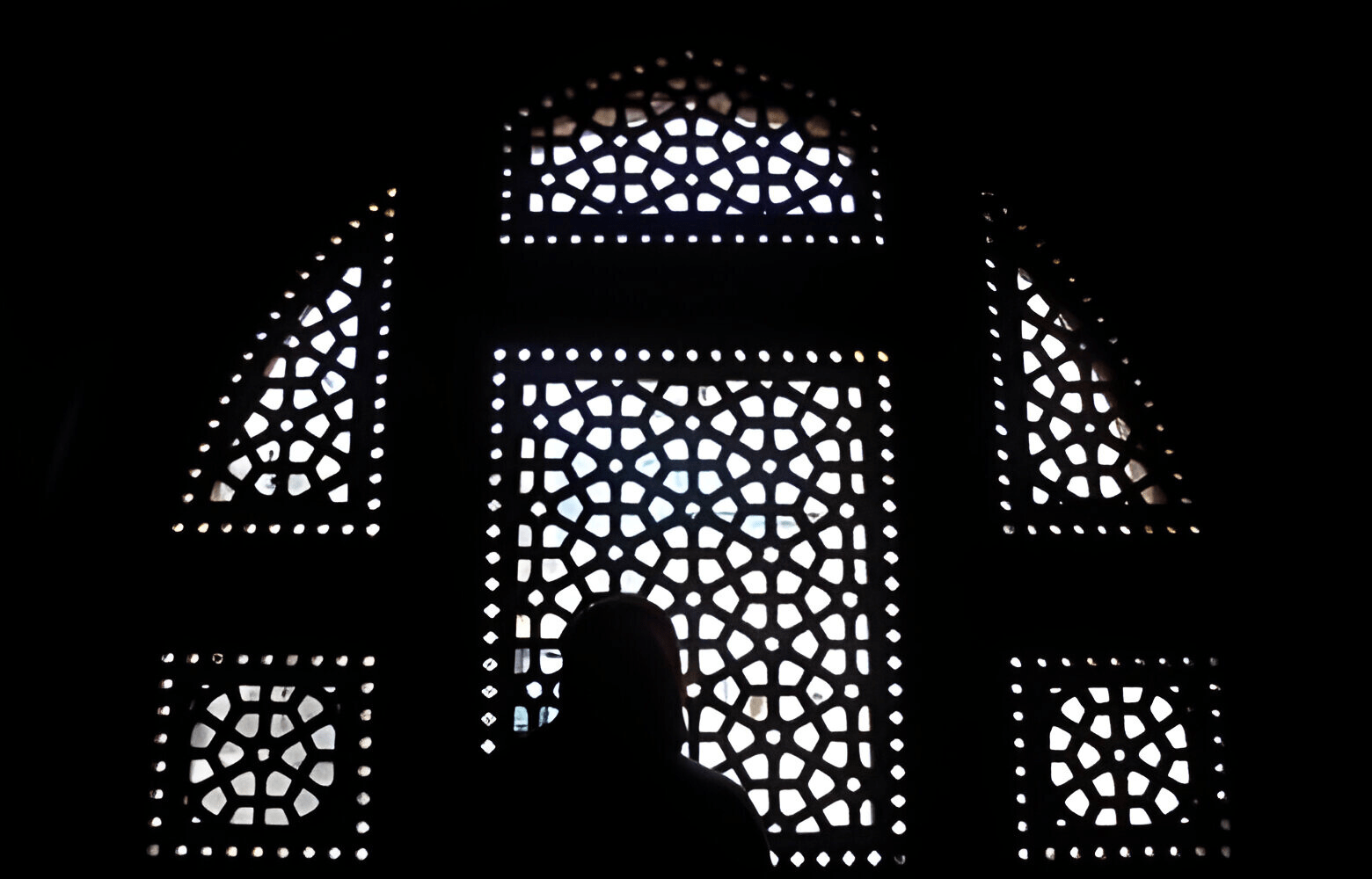

Nizamuddin and Khusraw continue to rule, from their graves, the hearts of the people of the land their forefathers adopted. Millions visit their dargah at Nizamuddin in Delhi where Hindavi qawalis of Khusraw to his Mehboob-e ilahi are sung every evening. Countless people pray at the dargah, tie threads to the jalis in the walls and make a special wish.

This fascinating era and the lives of the extraordinary characters who inhabited it present an absorbing case study of the contest between the sway of the sword and the power of love. It is illustrated through the lives of the two most formidable figures of the age – Alauddin Khilji and Nizamuddin. The prescient Khusraw wrote of the all-conquering Khilji:

When you cannot get more than 4 yards of land after your death

700 years later Khilji is remembered as a cruel figure who invites great ignominy. He lies buried, unknown to thronging tourists, in a quiet corner of the Qutub Minar complex in his 4 yards of space. The penniless Nizamuddin, by contrast, reigns supreme to this day. His dargah is a thriving complex where a million prayers are answered and countless hearts are healed.

Here lies an enduring message. It is as much for Khilji in his grave as it is for modern-day Sultans. The rule of megalomaniacal rulers, their narcissism and depravity, delusions of grandeur and eternal greatness will almost always be set right by the unsparing pen of history. Infamy will be their inevitable legacy. It is for the rulers of the heart and keepers of the soul that history reserves its greatest prize– one of everlasting reign and immortality.