The Poet and his Murshid – 1

History sometimes produces its great characters in pairs. This two-part series explores the lives of two of the greatest figures of the subcontinent – Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya and Amir Khusraw, the master and his murid.

Chengiz Khan’s Mongol hordes were undoubtedly the greatest scourge of history. As the unstoppable hordes swept across the world, bringing in their wake unspeakable death and destruction, those who could escape their wrath fled their homelands to safer havens. Central Asia was a special target of the Mongol fury. The two glittering cities of the Islamic world in the region, Balkh and Bukhara, were laid waste. Three families from these two cities, at different points of time in the 13th century fled their homes – one moved to Turkey and the other two to the western part of present-day Uttar Pradesh in India. This displacement from Central Asia caused by the violent hordes would birth some of the greatest figures of peace and spirituality in human history. The fleeing family that sought refuge in Turkey would produce possibly the best-known Sufi Saint today – Jalaluddin Rumi. The families of those who fled to India would produce equally exalted saints. From one family would spring, Nizamuddin Auliya, a colossal Sufi figure and from the other Amir Khusraw, a poet like none other. The two, murshid and murid, formed an inseparable pair and even 700 years after they were interred in their graves, the influence of the two looms large over the country adopted by their families. This story is of the indelible impression left behind by the pair on the consciousness of a nation.

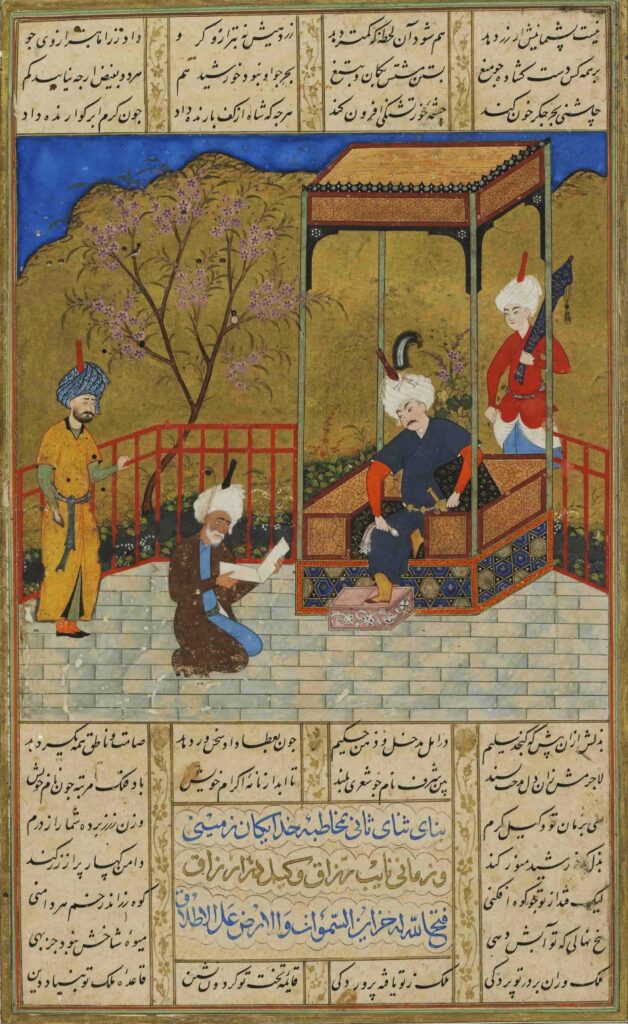

Before going into the characters of the story it is important to picture the period they lived in. The first Islamic empire in India, the Slave dynasty, came into being in 1192, six decades before the birth of Khusraw. As Islam gained its foothold in the subcontinent under the Slave dynasty and the succeeding Khilji and Tughlaq dynasties, political and religious power structures evolved to accommodate the new faith. A dual power structure seemed to emerge with the political power lying with the Sultan and the spiritual with Sufi mystics. The Sultan, who ruled in the name of Allah, required the support of the spiritual leader to legitimize his authority. The colossal figure of Nizamuddin, emerged as the spiritual power centre whose authority even the most powerful Sultan recognized. He never allowed any emperor to visit his Khanqah (lodge or hospice), nor went to any Sultans durbar. Though often wary of his authority, most Sultans did not dare to challenge it. Those who did, according to the colourful accounts of the period, seemed to hasten to their graves. Khusraw as the Court poet and closest confidant of Nizamuddin was in a unique position for he straddled both the imperial and the spiritual worlds. He in fact was a bridge between the two worlds.

By the time of Khusraw’s birth in 1253, Delhi, as the capital of the Sultanate, had emerged as an important cultural and intellectual centre which attracted the finest poets, writers, scholars and mystics. The renowned contemporary historian Ziauddin Barni would write ‘the capital of Delhi, by the presence of these peerless men of extraordinary talents, had become the envy of Baghdad, the rival of Cairo and the equal of Constantinople”. It was in this age of literary ferment in Delhi that the young prodigy, Khusraw, found his moorings. Unlike his murshid, Khusraw was born to privilege. His father, whose family had migrated from Balkh, was an officer of some standing in the pay of the Slave Sultan, Iltutmish. Khusraw’s father died when he was only eight and he was then taken under the wing of his maternal grandfather, a senior noble of Iltutmish’s court and later War Minister of Balban. Khusraw, who was tutored at home, showed an extraordinary talent for poetry at a very young age. He recounts a meeting with a leading scholar of Delhi, Khwaja Izzuddin. Khusraw’s tutor, proud of his pupil’s precociousness, asked him to recite some verses to the Khwaja. Khusraw recounted somewhat immodestly “I recited each verse in a tremulous and modulated accent so that my melodious recital rendered all eyes tearful, and astonishment surge on all sides”. The impressed Khwaja then “tested me with four discordant things, namely hair, egg, arrow and melon. In the presence of all in the assembly there and then I composed the following:

Every strand of hair in the curly tresses of that beauty

Has attracted a thousand grains [eggs] of amber.

Know her heart to be as straight as an arrow,

For like the melon the choice part is found inside.

The khwaja was astonished and predicted future greatness for the adolescent poet. Khusraw’s gift for wordplay and quick wit would be an enduring feature of his literary work.

The dour Slave Sultan, Balban, did not approve of poetry but such was the fervor for literature in Delhi that his nobles, who ran their own mini-courts, competed for the best poetic talents. The child prodigy, now a budding youth, was, therefore, much in demand. Khusraw served in the court of two of Balban’s sons and one of his nephews. As the finest poetry flowed from his pen, his reputation soared and it was only a matter of time before he would become the poet laureate in the court of the Sultan. Khusraw would hold this position under five Sultans of widely varying character and temperament – the hedonist Kayqubad, the genial Jalaluddin Khilji, the formidable Alauddin Khilji, the eccentric Mubarak Shah and the redoubtable Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq. It is a tribute to Khusraw’s even temperament and adaptability that he managed to find the favour of such varied despots.

The modern reader would find it strange to comprehend the one role that medieval royal poets had to play – that of a panegyrist. Writing panegyrics (odes or qasidas) to the supreme ruler was an indispensable part of the poet’s job. Sultans of all hues reveled in the elegant poetry that poets penned in praise of the shadow of God on earth. Generous rewards normally followed. One of the more stinging criticisms of Khusraw is his effusive praise, in the most sublime words, of all emperors, good and evil, that he served. The defence of most poets was that royal patronage secured a poet’s finances and allowed him to work unhindered on his craft. Writing panegyrics, therefore, was a sort of a necessary evil.

Khusraw was a Persian poet of the highest pedigree. Persian courts represented the high culture in the Islamic world and their refined tastes were held in awe by Islamic kingdoms everywhere. It was difficult for a person outside of Persia to acquire a reputation in Persian poetry. Khusraw, however, was an exception as he was held in high esteem in this Mecca of cultural refinement. He was as widely read in Isfahan and Shiraz as in India. The famous Persian poet of the age, Sadi, was fulsome in his praise of Khusraw’s poetry. The historian Ziauddin Barni, who was also a friend of Khusraw, wrote of him “There were poets in the reign of Sultan Alauddin Khilji such as had never existed before and have never appeared since. The incomparable Amir Khusraw stands unequalled for the volume of his writings and the originality of his ideal; for, while other great masters of prose and verse have excelled in one or two branches, Amir Khusraw was conspicuous in every department of letters. A man with such mastery over all the forms of poetry has never existed in the past and may perhaps not come into existence before the Day of Judgment”.

Khusraw’s body of work in Persian is enormous but it is not so much this that endures his legend in the subcontinent as the other aspects of his genius: his poetry in Hindavi, gift for wordplay, birthing of ghazals and qawalis, the renditions of his Hindavi poetry in these musical genres and his invention of musical instruments. It is to these that we now turn.

Interestingly, while his works in Persian can definitively be attributed to him, none of his Hindavi poetry, pahelis(riddles) and musical contributions can be traced to an authentic source. The Hindavi poetry of Khusraw, whose musical renditions are a part of the contemporary cultural landscape, have no definitive origin. No text written by Khusraw in Hindavi survives yet his poetry thrives. Oral tradition seems to have passed it down the centuries with compilers of a later day attributing these to Khusraw. While these verses may not be attributable to an authentic source, and not all of them may belong to Khusraw, his stamp is unmistakable. Sufi poetry is often characterized by a lover, usually the woman, pining for her beloved. The love between the two is a metaphorical expression of the love of a believer for God; the pining a yearning for a mystical union with the creator. In much of his poetry, Khusraw expresses his love for his master, Nizamuddin, in place of the creator. Another distinctive Khusraw feature is the use of Indian themes when representing this love: Indian seasons, colours, festivals and earthy settings.

Hindavi, a mix of Khari Boli and Braj Basha, originated in the eleventh century. It was still in its infancy in Khusraw’s time and he seems to have contributed to its development. As a mass poet, Khusraw’s Hindavi poetry and pahelis were popular and therefore very likely contributed to the growth of the language. Hindavi, which emerged as the lingua franca of large swathes of North India, is regarded as the forerunner of both Hindi and Urdu.

Doubts are cast on the pahelis attributed to Khusraw, but this attribution is not without a basis. Khusraw’s quick wit and gift for wordplay, a telling signature of his work, find their place in these pahelis. An example would explain the enduring popularity of Khusraw’s pahelis.

I saw a wonderous child in the land of Hindustan,

His skin covered his hair and his hair his bones.

Answer: Mango

The genius of Khusraw was not limited to the letters. If all his attributed contributions to Indian music are indeed true then his musical genius nearly matched his poetic finesse. It is said that Khusraw humbled the famous Deccan musician, Gopal, in a contest thus acquiring the title of Nayak, the highest honorific for a musician. The ghazal, a form of poetry with defined rules of rhyme, refrain and meter, is regarded by many historians as an invention of the famous Persian poet Sadi but it is Khusraw who introduced it in India. He is widely regarded as its finest exponent and also credited with rendering it in a musical form. The invention of Qawali, a musical rendition of sufi verses, which continues to be popular in contemporary culture, is also ascribed to Khusraw. His contribution to Indian melodies sounds even more astounding. Mirza, his biographer, writes “According to an old Persian work on Indian music he invented the following new melodies: mujir, sazgari, aiman, ushshaq, muwafiz, ghazan, zilaf, farghana, sarpada, bakharz, firodast, munam, qaul, tarana, khayal, nigar, basit, shahana and suhila”. The invention of the ubiquitous Indian instruments, Sitar and Tabla, are also ascribed to Khusraw.

Khusraw, who earned the sobriquet Tuti-i-Hind – the Parrot of India, appears to be the fount of so much of Indian culture: Hindi and Urdu, ghazal and qawali, khayal and tarana, sitar and tabla. Even if half of what is ascribed to Khusraw is true, his contribution is truly staggering. There are very few figures in history who have left behind cultural footprints which are so immense and enduring that they are visible even centuries later.

No painting of Khusraw can be complete without his murshid, Nizamuddin. We turn to this remarkable figure in the second part of the series.