The Sufi and the Zil-i-Ilahi – I

In democracies it is the will of the people that provides legitimacy to a Sovereign’s rule. In pre-democratic polities, often it was God who played this role. Starting with the first Islamic dynasty in India, Emperors often projected themselves as the Zil-i-Ilahi (God’s shadow on earth). This series explores the fascinating relationship between the Sufis, Islam’s greatest ambassadors in India, and the Zil-i-Ilahi.

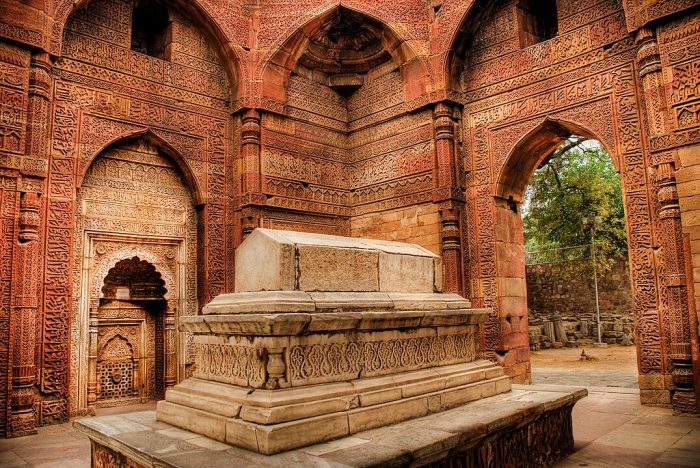

The road from Aurangabad to the famous Ellora caves forks at a point a few kilometers short of the monuments. A signboard indicates the road on the right leads to the tomb of Aurangzeb Alamgir, the most infamous of the Mughal emperors. The grave of the emperor lies in the town of Khuldabad, abode of paradise, which houses the tombs of some of the most revered Decanni Sufis. The resting place of Aurangzeb, in sharp contrast to the grand tombs of his illustrious ancestors, is remarkably simple. The pious Aurangzeb, who stitched prayer caps to fund his tomb, willed his grave should be open to the sky and shorn of all ostentation. The simplicity of the tomb, therefore, is unsurprising. What is surprising is the company he chose. He is buried in the tomb complex of Shaikh Zianuddin Shirazi and its eastern wall adjoins the grave of Burhanuddin Gharib. Burhanuddin Gharib, who was a Khalifa (disciple) of Nizamuddin Auliya, is credited with establishing the Chishti order of Sufism in the Deccan. Zianuddin was the follower of Gharib.

Why would the most puritanical of Mughals chose to bury himself in the company of Sufis. Sufism is widely perceived today as a liberal strain of Islam. Why would the puritanical cohabit with the liberal? Did that age not see any contradiction between the two. Who were these Sufis of the medieval ages who seemed to hold sway over even the mightiest emperors? This article examines these questions and seeming paradoxes. It seeks to understand the relationship between the Sufi and the Emperor.

The birth of the Zil-i-Ilahi

The year 1192 is a decisive year in the history of India as it heralded the advent of Islamic rule in the subcontinent. Mohammad Ghori, the Turkish ruler from Ghor in Afghanistan, defeated the Rajput ruler, Prithviraj Chauhan, and laid the foundation for the establishment of the Slave dynasty in India. The rule of the Slave dynasty does not receive the same attention in history books as some of the later dynasties. This period, however, is seminal as it would lay the foundation of political and religious structures in India that would determine the course of the following centuries. While the political structure does not survive, the edifice of the religious and spiritual foundations endures to this day.

The Slave dynasty acquires its name from the three most influential rulers of the dynasty who were all slaves – Qutubuddin Aibak, Iltutmish and Balban. Mohammad Ghori followed an emerging tradition in the Turkic regions where a slave could rise to become a ruler. It was a remarkably meritocratic society and the heirless Ghori when asked who would succeed him, remarked “Other kings have only a few sons, but I have several thousand sons, namely my Turkish slaves, who will rule my kingdom in my name after I am dead and gone.” Ghori was true to his word and his empire was split between three of his slaves.

Subsequent to the death of Prophet Muhamad, a politico-religious institution, the Caliphate emerged in the Islamic world. The Caliph (Khalifa or successor to the Prophet) exercised both spiritual and temporal authority. The Prophet, however, had not envisaged such an institution. Owing to the uncertainty surrounding the qualifications for a Caliph, the position was almost always held by a person either directly related to the Prophet or having kinship ties to him. The Caliphs held sway in the Islamic world for a considerable period but by the second half of the 10th century the Caliphate of the Abbasids, who claimed descent from an uncle of the Prophet, was in decline.

Around the same period, the Turkic regions of Central Asia were increasingly imbibing elements of Persian culture, including the pre-Islamic Persian view of the ruler as a divine figure. Mahmud Ghazni, the formidable Turkic ruler of the 11th Century (who, it appears, was the first ruler to take on the title of a Sultan), according to historian K.A Nizami “…… strutted like an absolute autocrat. He was the shadow of God on earth (Zil-i-Ilahi).” Ghazni continued to pay nominal obeisance to the Caliph but by effectively pronouncing himself as the Zil-i-Ilahi, he had delivered the first cut to the umbilical cord tying Islamic rulers to the Caliph. The concept of an Islamic ruler who was God’s shadow on earth, even though he was unrelated to the Caliph, was born. The Slave rulers of Delhi, drawing inspiration from this Turkic practise, too would declare themselves as Zil-i-Ilahi.

Ascent of Sufis in India

Concurrent to these developments in the 10th and 11th centuries was the rise of Sufism in Central Asia and Iran. Sufism would find its way into India during this period. With the advent of the Slave dynasty in the 13th Century many Sufi orders established themselves firmly in India. Two of these orders gained special prominence.

It was one thing for a ruler to declare himself as the shadow of God and quite another to have the subjects accept this audacious claim. Even the most formidable of these rulers realized that divinity was not something that could be thrust down people’s throat. They looked for legitimacy for this impudent claim.

Sufi saints, in a short period of time, had acquired an enormous following. This contemporary description shows the scale of popularity of Farid, the colossal Sufi of the Chishti order “In the month of Shawwal, 1252 AD, Sultan Nasiruddin marched towards Uchch and Multan. In the way his soldiers decided to pay their respects to Shaikh Farid. When the soldiers flocked to the city all the streets and bazaars of Ajodhan (Farid’s hometown) were blocked. It was impossible to shake hands and bless personally every one of these soldiers. A sleeve of Baba Farid’s shirt was hung on a thoroughfare so that people might touch and go. As the crowd moved, the sleeve was torn to pieces. The Shaikh himself was so painfully mobbed that he requested his disciples to encircle him in order to save his person from the eager public trying to elbow its way to him.”

Emperors, megalomaniacal and spiritual alike, acknowledged the power of the Sufis. Support of the Sufis for the ruler could legitimize the rule of the Zil-i-Ilahi. This would become the foundational basis for the relationship between the Sufi and the Emperor.

The word Sufi is generally regarded as having originated from the word suf, Arabic for wool, which was the preferred dress of renunciants in many parts of the world. Scholars differ on when Sufism originated but many trace its origin as far back as the time of the Prophet. Historian K.A Nizami identifies 3 stages in the development of mystical movement in Islamic 1. Period of the quietists (660 to 950 AD) 2. Period of Mystic philosophers (from the second half of 9 Century) 3. Period of silsilahs. Sufism is not easy to fit into a definition and so for the purpose of this article this simple description offered by Historian Rizvi is quoted “Sufism represents the inward or esoteric side of Islam: it may, for the sake of convenience, be described as the mystical dimension of Islam.”. It was during the second stage mentioned above that works on mystical philosophy were first written down and a systemic account of mystic philosophy put in place. While the list of the contributing philosophers to this growing body of literature is endless and an attempt to identify the most influential fraught with risk, the three most significant figures possibly were Imam Ghazali, Shaikh Ibn-i-Arabi and Shihabuddin Suhrawardy

Shihabuddin Suhrawardy’s Awarifu-ul-Maarif, according to SA Rizvi was, “the second most important Sufi textbooks on which the early Indian and Sufi doctrines and practices were based”. The follower of this Saint, Bahauddin Zakariya, established the Suhrawardy Sufi order in India. By the 13th century, fourteen silsilahs or orders of Sufism had been formed in the Islamic world and India became home to some of the most influential of these Sufi orders. The two most significant orders, which would have far reaching impact on the subcontinent, were the Suhrawardy and the Chishti.

The fate of these two orders, which emerged during the reign of the Slave dynasty, were intertwined with the fortunes of the Sultans. While one is accustomed to reading of the provinces and boundaries of an empire this period is unique as the Sufi orders established their own Wilayats or spiritual provinces. Khalifas trained by the Sufis masters would spread to different provinces of the country and establish their Wilayats. These Khalifas “in their turn, appointed subordinate khalifas for qasbhas and towns. Thus, a hierarchy of saints came to be established. The chief saint stood at the apex of the whole system and controlled a network of khanqahs spread over the country” Their writ ran large in these areas and people flocked to their khanqahs (hospice). The shrines of these Sufis flourish even today.

The dizzy rise of these Sufis paralleled the rapid ascent of the Delhi Sultanate. The ascent of the Sultans could be attributed to the sword. What explained the rapid rise of the Sufis?

An interesting story around Iltutmish, slave, son in law and successor, of the founder of the Slave dynasty illustrates, the enormous power of Sufi saints even in the early days of the Sultanate. Iltutmish, in these fledgling days of the dynasty, was trying to consolidate his hold over north India. Sindh, along with Multan in Punjab, was under the rule of Qabacha, another former slave of Ghori. As a conflict between the two seemed imminent various factions began to cast their support in favour of one of the two contenders. Bahauddin Zakariya, whose nascent and increasingly popular Suhrawardy order, had its Wilayat in Multan, threw in his lot with Iltutmish. He wrote a letter to Iltutmish expressing support which was intercepted by Qabacha. An infuriated Qabacha contemplated his execution. But even this formidable successor of Mohammad Ghori did not have the courage to invite the wrath of an enormously popular Sufi. Iltutmish ultimately prevailed in the battle with Qabacha. The stories in the bazaars could not help attribute the mysterious powers of the Sufi to Iltutmish’s victory.

The popularity of the Sufis was not surprising. In the land of the twice born castes, members of the humbler order were outside the pale of the society. The greatest ambassadors of a new faith, who made no distinction between people, would have had an immediate appeal. All were welcome to the Khanqahs. Langars (Free meals), which were served alike to the twice born and lesser beings, nobles and commoners, lettered and illiterate, were a great leveler. Sufis made few demands of their followers. The pressures of a puritanical faith were largely absent. The message that the Sufis preached was simple and very often conveyed through relatable and engaging anecdotes. The preferred medium of communication was the vernacular. These messages were often rendered in musical form, such as the qawwali, and this made them even more appealing.

Another reason for the popularity of the Sufis was the belief in their ability for Karamat (miracles). Even though some Sufis like Nizamuddin clearly denied having such powers the enormous faith of the people could not be persuaded otherwise. Sick and infirm, old and infants, rich and poor flocked for remedying ailments which the science of the age was incapable of curing. Stories of Sufis curing the infirm spread thick and fast adding to their aura.

It was the recurring stories of the curse of the Sufis, however, which gained the most currency. There are many stories, most likely apocryphal, of a Sufi cursing a recalcitrant Sultan. The Sultan was powerless against the curse and very often paid with his life. Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, Feroz Shah Tughlaq, Sikandar Lodhi, if the accounts are to be believed, all suffered fatally because they crossed the Sufis path.

While the power wielded by the Sufis was enormous it would be incorrect to assume that the Emperor viewed the Sufi only as an instrument for legitimizing his rule or a figure whose curse had to be feared. Many emperors were devoted followers of the Sufis. This touching story of Iltutmish shows how far a Sultan could go in demonstrating his reverence.

Iltutmish’s court in Delhi had become a magnet for scholars, writers, poets and holy men. The Chishti order, by this time, had established itself as the primary order among Sufis and its Saints, especially the founder Moinuddin Chishti, were held in great awe. Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, who was Moinuddin’s chosen successor, was offered the position of Shayakh-ul-Islam by a reverential Iltutmish who was overawed by his presence in Delhi. But the Sufi, in line with his Silsilah’s philosophy of staying away from the trappings of power, refused the offer. Iltutmish then conferred the position to an undeserving Shayakh whose vanity and conceit made him extremely intolerant of Bakhtiyar Kaki. Moinuddin Chishti was hurt by this treatment of his Khalifa and decided to leave for Ajmer with Bakhtiyar Kaki. Many citizens of Delhi, shattered by the departure of the saints, followed them on the journey to Ajmer. Iltutmish, too, joined the crowd. Moinuddin was touched by the gesture of Iltutmish and allowed Bakhtiyar Kaki to return to Delhi. An overjoyed Iltutmish expressed his gratitude by kissing the feet of Moinuddin. He then escorted Bakhtiyar Kaki back to Delhi.

This article attempted to define the contours of the relationship between the Sufi and the Emperor – the rulers of the spiritual and political empires. The following parts of this series will examine in greater detail the different Sufi orders, their chief actors and the fascinating relationship of these orders with succeeding Islamic dynasties in India.